- Scientists described numerous new species this past year, the world’s smallest otter in India, a fanged hedgehog from Southeast Asia, tree-dwelling frogs in Madagascar, and a new family of African plants.

- Experts estimate that fewer than 20% of Earth’s species have been documented by Western science, with potentially millions more awaiting discovery.

- Although species may be new to science, many are already known to local and Indigenous peoples and have traditional names and uses.

- Upon discovery, many new species are assessed as threatened with extinction, highlighting the urgent need for conservation efforts.

A giant anaconda, a vampire hedgehog, a dwarf squirrel, and a tiger cat were among the new species named by science in 2024. Found from the depths of the Pacific Ocean to the mountaintops of Southeast Asia, each new species shows us that even our well-known world contains unexplored chambers of life.

This year, in Peru’s Alto Mayo Landscape alone, scientists uncovered 27 new-to-science species, including four new mammals, during a two month expedition. Meanwhile, the Greater Mekong region yielded 234 new species, and scientists from the California Academy of Sciences described 138 new species globally. The ocean depths continued to surprise, with more than 100 potentially new species found on an unexplored underwater mountain off Chile’s coast. Two new mammal species were found in India this year, including the world’s smallest otter.

Scientists estimate only a small fraction of Earth’s species have been documented, perhaps 20% at best. Even among mammals, the best-known group of animals, scientists think we’ve only found 80% of species. Yet most of the hidden species are likely bats, rodents, shrews, moles and hedgehogs.

However, while species may be new to Western science, many have been well known to Indigenous peoples and local communities for generations. These communities often maintain sophisticated classification systems and deep ecological knowledge about species’ behaviors, uses and roles in local ecosystems.

“For example, the blob-headed fish, which is so bizarre and unusual, and scientists have never seen anything like it, but it’s very familiar to the Awajún,” Trond Larsen, the leader of the Alto Mayo expedition in Peru from the NGO Conservation International, told Mongabay. “They regularly catch and eat them.” Similarly, the ghost palm, newly named by scientists this year, has been used by Iban communities in Borneo for basketry and food for decades.

Unfortunately, many species may be threatened with extinction before they’re even formally named, victims of human activities like development and climate change. Some of these species could be foods or medicines for humans, but each has a unique role in Earth’s interconnected web of life.

“There is something immensely unethical and troubling about humans driving species extinct without ever even having appreciated their existence and given them consideration,” Walter Jetz, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Yale University, U.S., told Mongabay.

Here’s our look at some of the new-to-science species described in 2024:

Vampire hedgehog and glamorous viper among 243 new species from the Greater Mekong

The Greater Mekong region revealed some of the year’s most distinctive species. Local nature enthusiasts and researchers documented a hedgehog species with fang-like teeth, leading to its name vampire hedgehog (Hylomys macarong).

They also described a pit viper (Trimeresurus ciliaris) whose scales create the appearance of dramatic eyelashes, and a karst dragon lizard (Laodracon carsticola) first noticed by a local tour guide.

These findings illuminate the region’s rich biodiversity and conservation challenges, as many species face immediate threats from development and wildlife trafficking.

New giant anaconda species found on Waorani Indigenous land in Ecuador

A significant discovery has been made in the Ecuadorian Amazon, where scientists have identified a new species of giant anaconda in the Bameno region of Baihuaeri Waorani Territory. During their research, the team encountered an impressive female specimen measuring 6.3 meters (20.7 feet) in length from head to tail, though local Indigenous communities report encountering even larger individuals. The species faces multiple threats throughout its range, from deforestation destroying their habitat to direct hunting by humans and environmental degradation from oil spills.

Tree-dwelling frogs found in Madagascar’s pandan trees

In Madagascar’s eastern rainforests, three frog species living in pandan trees received their first scientific descriptions. Known locally as sahona vakoa (pandan frogs), these amphibians complete their entire life cycle within the water-filled spaces between the plants’ spiky leaves. The species, now given the scientific names Guibemantis rianasoa, G. vakoa and G. ambakoana, exemplify how local ecological knowledge often precedes formal scientific documentation by generations.

A new underwater mountain hosts deep-sea wonders off Chile</

An expedition in the Southeast Pacific discovered more than 100 potentially new-to-science species on a previously unknown underwater mountain, including deep-sea corals (order Scleractinia), glass sponges, sea urchins (class Echinoidea), amphipods (order Amphipoda) and squat lobsters (family Galatheidae).

The expedition also sighted rare creatures like the flying spaghetti monster (Bathyphysa conifera) and Casper octopus (genus Grimpoteuthis).

The seamount, rising about 3 kilometers (nearly 2 miles) from the seafloor, about 1,450 km (900 mi) off Chile’s coast, hosts thriving deep-sea ecosystems with ancient corals and glass sponges. The findings highlight the rich biodiversity of the high seas as the U.N. finalizes treaties to protect international waters.

Toothed toads emerge from mountain forests of Vietnam and China

Two new species of rare, toothed toads were discovered in Vietnam and China: the Mount Po Ma Lung toothed toad (Oreolalax adelphos) and the Yanyuan toothed toad (Oreolalax yanyuanensis). These amphibians are characterized by an unusual row of tiny teeth on the roof of their mouths. The discovery brings the total known toothed toad species to 21. However, more than half are already considered threatened due to habitat loss and degradation.

Dwarf squirrel and blobfish among 27 new species found in Peru’s Alto Mayo

In Peru’s densely populated Alto Mayo region, home to 280,000 people, scientists working with local communities documented 27 species previously unknown to Western science.

The species included an amphibious mouse (Necromys aquaticus) found in just one patch of swamp forest; a fish with an unexplained blob-like head structure (Trichomycterus sp. nov.); an agile dwarf squirrel (Microsciurus sp. nov.); and a tree-climbing salamander (Bolitoglossa sp. nov.). These findings demonstrate how even human-modified landscapes can harbor biodiversity not yet documented by scientists.

The clouded tiger cat gains species status

Scientists formally described a new small wild cat species, the clouded tiger cat (Leopardus pardinoides), found in high-altitude cloud forests from Central to South America. This taxonomic clarification has major conservation implications, as new data indicate all three tiger cat species have experienced dramatic range reductions, with the clouded tiger cat’s habitat particularly threatened by human activities.

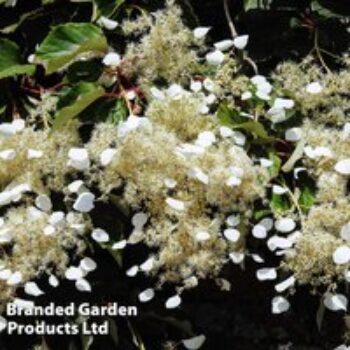

Though long used by local Iban communities in western Borneo for basketry and edible shoots, scientists finally gave a formal name to a distinctive rattan palm after 90 years. Named Plectocomiopsis hantu (“hantu” meaning ghost in Indonesian and Malay), the palm is known for its ghostly appearance, with white undersides to the leaves and gray stems. It’s currently known from only three locations in or near protected rainforest habitats.

A new family of African plants that can’t photosynthesize

Scientists named an entirely new family of plants, Afrothismiaceae, which have evolved to take all their nutrients from fungal partners rather than through photosynthesis. Found in African forests, these rare plants only appear above ground to fruit and flower. Most species in this family are extremely rare or possibly extinct, with the majority recorded only once in Cameroon.

The orchid family is immense, and new species are found most years. This year, researchers described five new species from islands throughout Indonesia. These are: Coelogyne albomarginata from Sumatra, Coelogyne spinifera from Seram, and Dendrobium cokronagoroi, the Dendrobium wanmae (a critically endangered species) and Mediocalcar gemma-coronae (endangered), all from western New Guinea.

A lonely liana faces extinction from cement production in Vietnam

A new genus and species of green-flowered liana, Chlorohiptage vietnamensis, was discovered in Vietnam but is already assessed as critically endangered. Its limestone karst habitat is being cleared for quarries to make cement, threatening the only known population of this unique plant.

Two new mammal species in were described in Kaziranga National Park and Tiger Reserve, Northeast India’s biggest national park. A forest officer documented the presence of the small-clawed otter (Aonyx cinereus), the world’s tiniest otter species. The small-clawed otter, protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act 1972, joins two other otter species already known to inhabit Kaziranga.

The binturong (Arctictis binturong), an elusive nocturnal tree-dweller also known as the bearcat, was photographed by tour guide Chirantanu Saikia in January 2024. The binturong is found exclusively in Northeast India and requires dense forest canopy for survival. It has become increasingly rare due to deforestation.

While local residents had previously reported sightings of both species, these photographs provide the first concrete evidence of their presence in the park. Conservation officials believe these discoveries suggest the potential presence of other undocumented species within the park, highlighting the importance of continued wildlife surveys and protection efforts in the region.

One of the tiniest frogs ever found in Brazil

Scientists in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest described a remarkable new species of frog, Brachycephalus dacnis, measuring just 6.95 millimeters in length – about the size of a pencil eraser. Unlike other similarly tiny frogs that often struggle with balance, this species has maintained its inner ear structure, allowing it to jump gracefully up to 32 times its body length. The discovery in São Paulo state’s remaining Atlantic Forest highlights both the region’s rich biodiversity and the urgent need for conservation, as this critically threatened ecosystem now stands at just 13% of its original extent, potentially harboring many more undiscovered species.

Banner image of Leopardus pardinoides, or the clouded tiger cat, as a new species. This small wildcat is found in the cloud forests of Costa Rica, south to Panama, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia and Argentina. Image courtesy of Johanes Pfleiderer.

Liz Kimbrough is a staff writer for Mongabay and holds a Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology from Tulane University, where she studied the microbiomes of trees. View more of her reporting here.

Gone before we know them? Kew’s ‘State of the World’s Plants and Fungi’ report warns of extinctions

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message directly to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.